Approximately 10-15% of the cases of macular degeneration are the “wet” (exudative) type, sometimes also referred to at neovascular macular degeneration or nAMD.

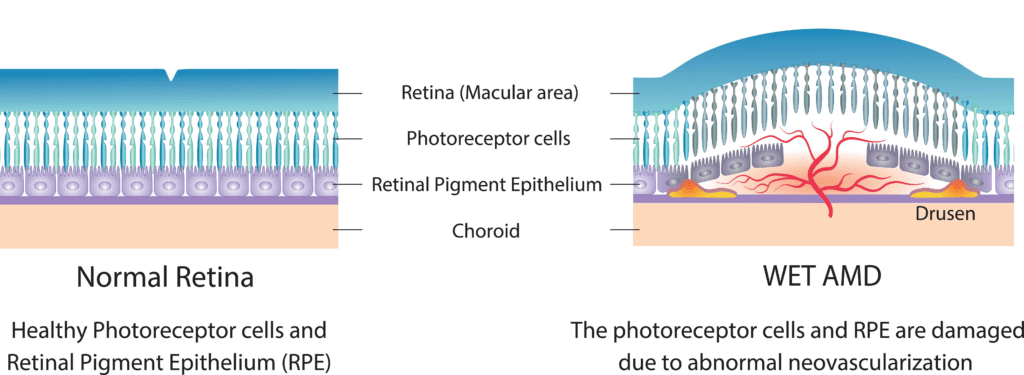

In the “wet” type of macular degeneration, abnormal blood vessels (known as choroidal neovascularization or CNV) grow under the retina and macula. These new blood vessels may then bleed and leak fluid, causing the macula to bulge or lift up from its normally flat position, thus distorting or destroying central vision. Under these circumstances, vision loss may be rapid and severe.

Symptoms of Wet Macular Degeneration

With the “wet” type of age-related macular degeneration, patients may see a dark spot (or spots) in the center of their vision due to blood or fluid under the macula. Straight lines may look wavy, or bent, because the macula is no longer smooth. Side or “peripheral” vision is rarely affected. Some patients do not notice any such changes, despite the onset of neovascularization (1). Therefore, periodic eye examinations are still very important for patients at high risk. And if you notice any sudden changes in your vision, you need to call your eye specialist immediately. Early intervention of any bleeding offers the best chance of preserving vision.

What the Patient may see:

Click here for a video describing what a person with macular degeneration sees.

Two Forms of Choroidal Neovascularization

There are two forms of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) that have been identified, “classic” and “occult.” The classic form is well-defined and usually results in vision that is between 20/250 and 20/400, but it may be worse than 20/800. For eyes with the occult form, the average visual acuity is somewhat better, between 20/80 and 20/200. Occult lesions are not well-delineated and they have less leakage (2).

Risk of the Development of Wet AMD

Once CNV has developed in one eye, whether there is a visual loss or not, the other eye is at relatively high risk for the same change. When all four risk factors—more than five drusen, large drusen, pigmental clumping, and systemic hypertension—are present, the five-year risk of CNV in the second eye is 87%, whereas if none of these risk factors are present, the risk is 7% (3).

In addition, CNV may progress rapidly, and any sudden change in central vision therefore requires a prompt examination after dilation of the eyes. The purpose of this exam is to find out whether the sudden loss of vision is due to leakage of blood vessels and which treatment may be appropriate.

Click here for a video presentation illustrating the development of macular degeneration.

Wet AMD Treatment

Unlike Dry AMD which can be slowed in many patients through lifestyle changes, supplements, and an AMD Diet, wet AMD cannot be slowed by natural remedies and needs to be treated as early as possible by a retina specialist. Controlling the bleeding is paramount to reducing retinal scarring that is responsible for severe vision loss.

Early, and sustained treatment has been shown to be the best course of action to preserve as much vision as possible for as long as possible if you have developed wet macular degeneration.

Current treatment options target controlling bleeding, with the accepted first line of treatment being Anti-VEGF drugs that control bleeding by stopping the growth of new blood vessels that tend to be leaky.

Current FDA approved anti-VEGF drugs include:

- Bevacizumab (Avastin).

- Ranibizumab (Lucentis).

- Aflibercept (Eylea).

- Brolucizumab (Beovu).

- Faricimab-svoa (Vabysmo)

These drugs are administered by eye injections at regular intervals. Your doctor will determine how often you need these injections based on your case, and the particular drug he/she has selected. Most patients need injections monthly. This helps sustain the effects of the medicine and helps slow and prevent further bleeding and scarring.

Anti-VEGF drugs do not restore vision, though some patients may experience a sense of vision restoration due to the body reabsorbing fluid behind the retina after the bleeding is stopped. But anti-VEGF drugs cannot repair retinal scarring, which is the main culprit of vision loss in wet macular degeneration.

Risks of anti-VEGF eye injections include:

- Conjunctival hemorrhage.

- Increased eye pressure.

- Infection.

- Retinal detachment.

- Eye inflammation.

Talk to your doctor about any concerns you have about the risks. But please remember that the earlier the intervention, the more vision you will be able to preserve. If you currently have Dry AMD, talk to your doctor about anti-VEGF before you develop wet AMD so you know what to expect and won’t have need to hesitate on getting treatments if the time comes.

To learn more anti-VEGF and other treatment options, click here.

Low Vision Rehabilitation

Age-related macular degeneration causes central vision loss. And while AMD doesn’t cause complete blindness, central vision is responsible for our sharpest, and detailed vision. Losing central vision has significant impact on your ability to carry out the daily tasks of living, from complex tasks like driving, to seemingly simpler tasks like writing a check to pay a bill. Ask your retina specialist about low vision rehabilitation to get a referral. Or, use Google to search for local low vision rehabilitation specialists, or occupational therapists. These specialists are specially trained to assess your vision loss, your needs, and then offer training to help you optimize your remaining vision with the use of low vision tools and modifications.

References

1. AM Fine, Earliest symptoms caused by neovascular membranes in the macular. Arch Ophthal. 1986;104:513-4.

2. MG Maguire, Natural history. JW Burger, SL Fine, MG Maguire, eds. Age-related Macular Degeneration. St. Louis: Mosby: 1999;17-30.

3. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Risk factors for choroidal neovascularization in the second eye of patients with juxtafoveal or subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthal. 1997;115:741-7.

Did you find this content helpful?

Would you like to be part of bringing this information to the public? All our educational materials, including this website, are made possible by individual donations from people just like you. If you have the ability to contribute, you can support these efforts.